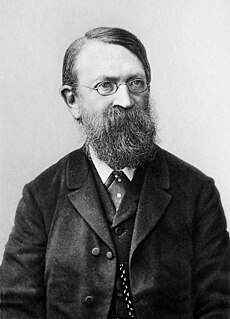

Nikolai Punin 1888-1953

(FROM wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nikolay_Punin)

In 1949 Punin was arrested on accusations of "anti-Soviet" activity, because he said that many thousands of Lenin's portraits are tasteless. The Soviet government punished Punin by imprisonment in the Gulag camp in Vorkuta, northern Russia. This time nobody could help Punin, because the intellectual elite of Leningrad was devastated by the Leningrad Affair. Most intellectuals who could help, were imprisoned, killed, exiled, or silenced by fear of Stalin's attacks.

A secret file on Nikolay Punin was created with numerous accusations of his anti-Soviet activity. Most accusations were fabricated by various agents of the former Soviet KGB office in Leningrad, such as Lt. Prussakov, who accused "former professor of Leningrad University and Academy of arts, Punin" of "anti-Soviet" propaganda. Punin's popular lectures about European artists, such as Rembrandt and Impressionists were seen by the communists as evidence of his anti-Soviet activity.[4]

In 1953, just months after Stalin's death, Nikolay Punin died in the Gulag camp of Vorkuta, after spending the four last years of his life under harsh conditions of cold and hunger, in an old barrack crowded with two hundred prisoners lit by one light bulb.

Legacy

Punin was known as "savior of art collections" because he protected many valuable paintings of western artists, which were labeled "decadent bourgeois art" by the communist propaganda. In doing so, Punin took many risks by raising his voice in opposition to the Soviet officials. As curator of the Hermitage Museum and the Russian museum Punin saved many important masterpieces of art from destruction by revolutionary mob and undereducated communists. He was severely attacked by the Soviet communists for his efforts in preservation of "Western" art in Soviet museums. He was respected by artists and intellectuals as the key figure in Russian art history.

Punin was also a remarkable lecturer; his lectures were extremely popular among open-minded members of the Soviet Academia, and among his numerous students.[5]

FROM: RUSSIAN ART OF THE AVANT-GARDE by John E. Bowlt

Lectures 5&6:

---

Poor man, he died in a gulag. Another example of how dictatorships exterminate creative and scientific activities.

FROM BOWLT:

--

(FROM wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nikolay_Punin)

In 1949 Punin was arrested on accusations of "anti-Soviet" activity, because he said that many thousands of Lenin's portraits are tasteless. The Soviet government punished Punin by imprisonment in the Gulag camp in Vorkuta, northern Russia. This time nobody could help Punin, because the intellectual elite of Leningrad was devastated by the Leningrad Affair. Most intellectuals who could help, were imprisoned, killed, exiled, or silenced by fear of Stalin's attacks.

A secret file on Nikolay Punin was created with numerous accusations of his anti-Soviet activity. Most accusations were fabricated by various agents of the former Soviet KGB office in Leningrad, such as Lt. Prussakov, who accused "former professor of Leningrad University and Academy of arts, Punin" of "anti-Soviet" propaganda. Punin's popular lectures about European artists, such as Rembrandt and Impressionists were seen by the communists as evidence of his anti-Soviet activity.[4]

In 1953, just months after Stalin's death, Nikolay Punin died in the Gulag camp of Vorkuta, after spending the four last years of his life under harsh conditions of cold and hunger, in an old barrack crowded with two hundred prisoners lit by one light bulb.

Legacy

Punin was known as "savior of art collections" because he protected many valuable paintings of western artists, which were labeled "decadent bourgeois art" by the communist propaganda. In doing so, Punin took many risks by raising his voice in opposition to the Soviet officials. As curator of the Hermitage Museum and the Russian museum Punin saved many important masterpieces of art from destruction by revolutionary mob and undereducated communists. He was severely attacked by the Soviet communists for his efforts in preservation of "Western" art in Soviet museums. He was respected by artists and intellectuals as the key figure in Russian art history.

Punin was also a remarkable lecturer; his lectures were extremely popular among open-minded members of the Soviet Academia, and among his numerous students.[5]

FROM: RUSSIAN ART OF THE AVANT-GARDE by John E. Bowlt

Lectures 5&6:

“Almost always critics pass judgment not on the work of art

but in connection with it…”

“First and foremost- we consider science to be a principle of

culture.”

“We must create a cohesion and reciprocity between the individual

person and individual groups of people so that relations between them will be

organized.”

PRINCIPLE OF ORGANIZATION

"We strive primarily in order that our whole world view, our

social structure, and our whole artistic, technological, and communal culture

should be formed and developed according to a scientific principle. In this

lies the characteristic difference between culture and civilization.

Man is a technological animal, i.e., in the new arrangement

of European society- which has not yet come about,but which is in evidence- man

must as far as possible economize his energy and must in any event coordinate all

his forces with the level of modern technology. In this respect the role of the

machine, as a factor of progress, is of course, immense in the modern artist’s

development.

The machine revealed to him the possibility of working with

precision and maximum energy; energy must be expended in such a way that it is

not dissipated in vain- this is one of the basic laws of contemporaneity that Ernst

mach formulated; the economy of energy and the mechanization of creative

forces- these are the conditions that guarantee us the really intensive growth

of European culture.”

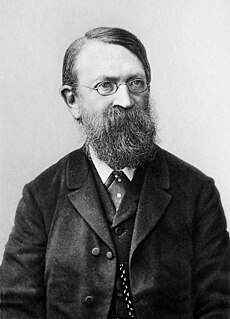

FROM WIKIPEDIA: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernst_Mach

Ernst mach

he and his son Ludwig were able to photograph the shadows of

the invisible shock waves.

Ernst Waldfried Josef Wenzel Mach (/ˈmɑːx/; German: [ˈɛɐ̯nst

maχ]; February 18, 1838 – February 19, 1916) was a Czech-Austrian physicist

and philosopher,

noted for his contributions to physics such as the Mach

number and the study of shock waves. As a philosopher of science, he was a major

influence on logical positivism, American pragmatism[5] and

through his criticism of Newton, a forerunner of Einstein's

relativity.

Gestalt psychology or gestaltism (German:

Gestalt [ɡəˈʃtalt]

"shape, form") is a theory of mind of the Berlin School of experimental

psychology. Gestalt psychology tries to understand the laws of our ability

to acquire and maintain meaningful perceptions in an apparently chaotic world.

The central principle of gestalt psychology is that the mind forms a global whole with

self-organizing tendencies.

“…mechanization becomes the general stimulus for creating a new artistic culture. Hence, naturally there arises the acute question of the

new artist’s attitude toward nature, because nature is something that

contradicts mechanization. Nature is something that introduces into the modern

world that peculiarity, that fortuity which is inherent in herself. Hence, the

new artist’s attitude towards nature is the touchstone of his world view.”

“We are formal. Yes, we are proud of this formalism because

we are returning mankind to those peerless models of cultural art that we knew

in Greece. Isn’t that sculptor of antiquity formal, doesn’t he repeat in

countless, diverse forms the same gods who ultimately for him are equally

alien, equally remote, inasmuch as he is an artist? And nonetheless, we love

these antique statues and delight in them- and we do not say they are formula. This

formalism is that of a classical, sound organism rejoicing in all forms of

reality and aspiring one to one thing: to reveal all its wealth, all the

tensions of its creative, elemental forces in order to realize them in works of

arts that would contain only signs of great joy- of that great creative tension

that is latent in us and bestowed on each of us, each of those who are born to

be, and MUST be artists.”

“...the closer the link between material and creative

consciousness, the more lasting the work of art the more breautiful it is- and

the less popular...”

********************************************************************************

********************************************************************************

“And indeed, when we come to study art history, when we

study our contemporary life and art, we convince ourselves time and again that

the material aspect of life is joined closely to the spiritual, and this is

this the mob cannot forgive the artist. The mob cannot endure this close

interdependence, the mob strives continuously to escape this purity of method-

pure insofar as the artist’s whole spiritual essence is expressed by distinct

material elements: the mob does not like purity and comprehends better works of

art whose material construcion is diluted by all kinds of other elements not

deriving directly from the sensation of painting or the sensation of plasticity. For the mob,

painting as a pure art form, painting as an element, is unintelligible unless it

is diluted with literary and various other aspects of artistic creation.”

********************************************************************************---

Poor man, he died in a gulag. Another example of how dictatorships exterminate creative and scientific activities.

FROM BOWLT:

Punin’s assertion that “modern art criticism must be … a

scientific criticism: served as a logical conclusion to a process evident in

avant-garde theory and criticism since about 1910 whereby the aesthetic balance

had shifted increasingly from a narrative, literary criterion to a formal

medium- oriented one […] Much in the formalist spirit, Punin even succeeded in

reducing the creative process to a mathematical formula:

S (Pi + Pii + Piii + … Pπ)Y=T

Where S equals the sum of the principles (P), Y equals

intuition, and T Equals artistic creation.

--

Publishing Information:

Russian Art of the Avant Garde Theory and Criticism Revised and Enlarged Edition edited by John E. Bowlt